19 Oct Percentage Entitlement In Family Law Case Short De-Facto Relationship

In the case of Grunseth & Wighton [2022] FedCFamC1A 132 (26 August 2022) an appeal was made from original orders dividing the parties’ property so the appellant (de facto wife) received 47.5 per cent and the respondent (de facto husband) received 52.5 per cent.

Background to case

The appellant contended that such a finding could not be made because she contributed over half of the property to be divided. There was only a small adjustment made by the original judge under s 90SF(3) of the Family Law Act 1975 (Cth). It was a short relationship.

On appeal it was found that there had been error established. Findings of family violence were open on the evidence as well. Each party sought the possession of a dog purchased by the appellant wife. Original orders were set aside so the matter could have discretion re-exercised.

Orders were made to adjust the split in sale proceeds upon the sale of the property so that the de facto wife received 70% les $160,000 which the de facto husband put towards the deposit of a property.

Orders made on appeal:

- The appeal is allowed.

- Orders 10(b), 14 and 15 made on 24 December 2021 are set aside.

- The following orders made on 24 December 2021 are varied as follows:

-

- Upon completion of the sale of the said property, the parties must pay the proceeds of sale in the following manner and priority:

(a) All costs and expenses of sale, including legal costs and disbursements, agent’s commission, advertising expenses, valuer’s fees and auction expenses, including repayment of any such expenses as have been paid by either of the parties;

(b) In discharge of any charges running with the land necessary to effect the transfer of the property;

(c) To divide the net balance between the parties as follows:

(i) The appellant receives 70 per cent less $160,800, and

(ii) The respondent receives 30 per cent plus $160,800

…

- The appellant is to retain all assets in her name and possession, and the following items:

(a) All items of furniture, whitegoods and furnishings located in the loft and main bedroom of the main dwelling of the said property;

(b) The dog “Patricia” registered in her name and in her possession and control; and

(c) The dog “Roxy” identified by microchip … , which dog is currently registered in her name and in her possession and control.

- The respondent is to retain all assets in his name and possession, and the following items:

(a) All items of furniture, whitegoods and furnishings located in the main dwelling of the said property, with the exception of the appellant’s furniture and furnishings located in the main bedroom which will be retained by the appellant.

- The respondent is to pay the appellant’s costs fixed in the sum of $12,000.

Reasons for Judgement:

“The parties met in 2004 and slowly developed a relationship which became a de facto relationship (as defined by s 4AA(1) of the Act) in late 2013.

At that time, they purchased a property in B Town (“the B Town property”) for $1,040,000, which was financed, in part, by a mortgage of $99,223.50. The appellant’s direct contribution to that purchase was $716,423.27, most of which came from the sale of a property previously owned by her.

The respondent contributed $320,000, of which $20,000 came from his savings and $250,000 as a gift from his mother. The respondent’s father also made an immediate payment towards the mortgage of $50,000.

The parties recognised these various contributions in the ownership of the home, which was registered in the name of the parties as tenants in common with 70 per cent held by the appellant and 30 per cent held by the respondent.

The respondent received inheritances in June 2015 of $750,000 and in September 2017 of $128,211.92, making a total of $878,211.92.

On 17 June 2015, the respondent paid out the balance of the mortgage in the sum of $43,846.42. In January 2016, the respondent paid the appellant $160,000. In short, the respondent’s evidence was that this was pursuant to an earlier oral agreement to the effect that if he made that payment, he would become a one-half owner of the B Town property.

The appellant agreed that the payment was for an increased share of the property but not for equal shares because of the increase in value of the property. She said that no percentage increase was ever agreed. No adjustment to the nature of the registered ownership was made.

The parties separated in October 2016, although they both remained living in the B Town property until November 2019.

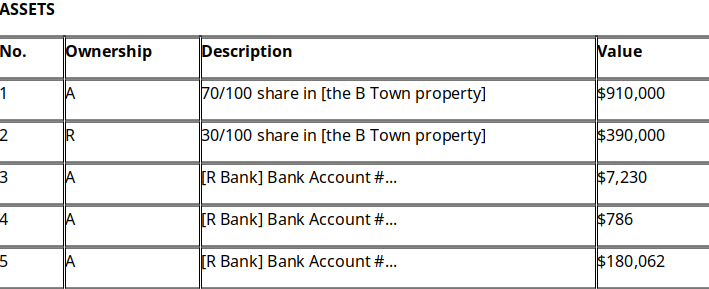

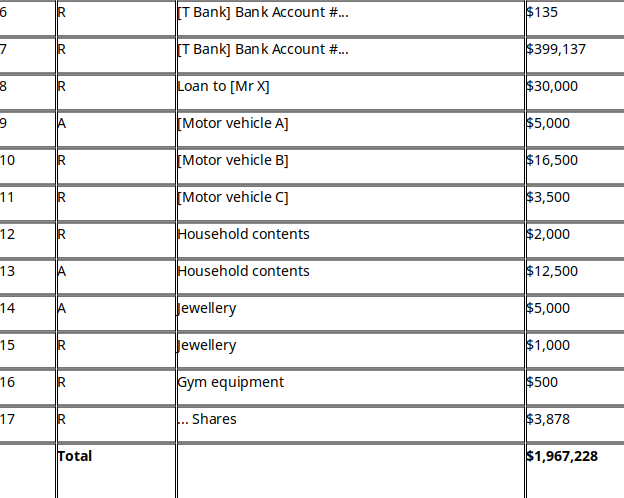

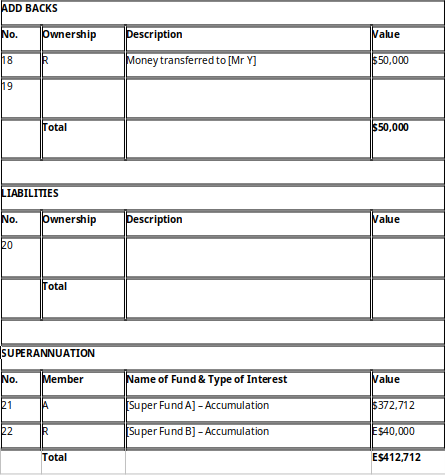

The period of the de facto relationship was, therefore, very short, being just under three years. There was no dispute about the property to be divided, save as to the sum of $160,000 already mentioned. The primary judge found it to be:

The total property available for distribution was $2,429,940 (noting that $50,000 which was transferred to Mr Y was notional only and no longer existed in the hands of the parties).

The parties did not suggest that either had made any relevant contributions to the other’s superannuation. That is not surprising given the short relationship. The evidence was that $150,000 of the appellant’s superannuation accrued after separation.

The payment of $160,000 by the respondent to the appellant is reflected in item 5 (the appellant’s bank account with a balance of $180,062).

The appellant’s primary submission is that, given it is accepted she contributed $910,000 as her share of the house and her superannuation of $372,712, a total of $1,282,712 or 52.79 per cent of the total property, the findings as to the appropriate division of the property are untenable. When the appellant’s other assets are included, but leaving out the sum of $160,000, the appellant’s property increases to nearly 55 per cent (54.87 per cent) of the total.

The submission continued, noting that the financial contributions during the relationship were equal, that the non-financial contributions favoured the appellant and that there was to be a slight adjustment in her favour under s 90SF(3) of the Act.

Post-separation Superannuation

The [respondent’s] superannuation at separation was $20,000 [… [60]]. It has increased only to approximately $40,000. This is a post-separation contribution to the pool of $20,000.

The [appellant’s] superannuation at 30 June 2016, a few months before separation, was $223,990. At February 2020 it was $372,712.

The majority of that period was post separation. That was, as the [appellant] submitted, a significant post-separation contribution of approximately $150,000 to the pool as a result of the [appellant] electing to increase her superannuation contributions at the cost of access to current disposable income.

Lump Sum Contributions – Summary

The [appellant] made a lump sum contribution to the relationship at cohabitation of $726,000, almost all of which went directly to the purchase of [Town B].

The [respondent] made lump sum contributions to the relationship totalling $1,198,211.92. $320,000 went to [Town B] at the time of purchase, $43,846.42 went to pay off the mortgage in June 2015, and $160,000 went to the [appellant] in January 2016.

Some of it he still holds and it is represented on the balance sheet. That was a total of approximately $1,924,000 in lump sum contributions.

Added to that the parties have accrued an additional $170,000 in superannuation between them post-separation and that is approximately $2,094,000 in identifiable financial contributions, or 86% of the total pool of $2,429,940.”

Contributions of the parties & calculations

“The parties were in a short de-facto relationship of 2 years and 9-10 months. The parties purchased [Town B] as to 70% to the [appellant] and 30% to the [respondent] based on their contributions of $726,000 by the [appellant] and $320,000 by the [respondent] in December 2013.

The [respondent] then contributed lump sums from inheritances totalling $878,211.92 over the following years. The timing of those payments is noted elsewhere. $43,846.42 of that went to pay off the mortgage in June 2015 and $160,000 to the [appellant] in January 2016.

The parties have accrued an additional $170,000 in superannuation post-separation, $20,000 contributed by the [respondent] and $150,000 by the [appellant].

That was approximately $2,094,000 in identifiable financial contributions, or 86% of the total pool of $2,429,940. In the context of a short relationship, these are a significant factor to be taken into account, noting also the timing of the different contributions.”

Did the primary judge err by failing to make the findings of family violence sought by the appellant? (Ground 6)

“There is a long line of authorities in the High Court of Australia that point out that where the advantages of a trial judge play a part in determining what evidence is to be accepted, that finding can only be challenged in limited circumstances, such as where the trial judge has misused his or her position or where the findings are contrary to incontrovertible facts or compelling inferences or are glaringly improbable.

See, for example, Robinson Helicopter Co Inc v McDermott [2016] HCA 22; (2016) 331 ALR 550; Lee v Lee [2019] HCA 28; (2019) 266 CLR 129.”

Did the primary judge err in “failing to take account the expert evidence of Professor N”? (Ground 7)

Did the primary judge err in “failing to take account the expert evidence of Professor N”? (Ground 7)

“Professor N is a psychiatrist who provided a report in which he opined that the appellant had a post-traumatic stress disorder (“PTSD”) which was consistent with the family violence she had described to him.

The primary judge said:

Because of the view I have formed that the [appellant’s] evidence on her mental state and the alleged impacts of family violence on her is unreliable, and as [Professor N’s] opinion can only be as good as the factual foundation on which it is based, I will deal with his opinion in as much detail as I usually would.

Such an approach is entirely in accord with the authorities such as Makita (Australia) Pty Ltd v Sprowles [2001] NSWCA 305; (2001) 52 NSWLR 705.

The appellant also submitted that the finding of Professor N that she had PTSD bolstered her evidence because there was no other explanation for the disorder.

However, as Professor N’s report makes plain, it is based on an acceptance of the appellant’s allegations (Affidavit of Professor N filed on 9 July 2019, Annexure “A”, p.8).

This ground does not succeed.”

Appeal successful and costs ordered

“The appeal has been partially successful, although a number of grounds have failed. However, quite properly, there was little that counsel could say on the grounds raising the error as to the contributions. The appeal should have been conceded at an earlier time. Given that, and the amount claimed by the appellant in her costs schedule, the respondent will be ordered to pay the appellant’s costs fixed in the sum of $12,000.”

Where do I stand?

If you would like a complimentary up to half hour phone consult with a lawyer to see where you stand with your family law property entitlements, book a call with Rigoli Lawyers – make your free booking by calling 03 8742 3199 Clients from all Australian States welcome.

Where do I stand?

Book a call to talk to a lawyer.